Business Process Management - The Third Wave25th of Januari 2016One of the works listed as a must-read in the OMG BPM Fundamental certification exam, this book, written by Howard Smith and Peter Fingar in 2002, laid out the history of BPM in the 20th century and attempted to predict the evolutions over the next 50 years in the discipline. They divvy up the last century in three big waves:

The introduction gives an overview of the predominant concepts of BPM at the time of publication. The clue is to follow in the footsteps of Walt Disney when he says that, if you do something exceedingly well, people will pay you to do it again. Pair this off with Michael Hammer’s observation that tackling business process reengineering without keeping a focus on the customer, is like operating without a safety net. And for incumbent enterprise to survive market disruptions, they need to adapt, which is made considerably easier when their processes are made explicit. |

|

The first chapter tries to put the finger on the pitfalls raised up till the 21st century. Companies trying to jump on the BPM bandwagon, and describing their processes in excruciating detail, only to lock them away in vaults, could be considered the primordial amongst all pitfalls. The inflexibility of business processes in existing firms is a second sore point. As Peter Drucker points out, this can cause the loss of the first mover advantage, since newcomers in the market can immediately start their processes attuned with the market conditions. Not only does the need for flexibility exist (both proactive and reactive), but there is also the aspect of time. It happens too often that technical implementations are started before a complete business impact was assessed, and vice versa the technical details could obscure the changes on the business level, and might even cause that ownership of the process shifts to the technical team, where it doesn’t belong. It is clear that business needs to take ownership of their processes, and the changes made to them. Technology will have to be able to follow. Paul Strassman states this as the transition of BPM from technology to economics.

The current affairs of IT however are still too fixated on data, and the fact of the matter is that computers at this point seem to be record-keeping automatons, and not management machines. We need to move this towards actionable information. This is where the context created by business processes should play its part. The 21st century needs to tackle the objectives Peter Drucker set out in his work “Management Challenges for the 21st Century”, namely a systematic and organized method for obtaining information about the context of the business in the economy, its markets, and its pool of competitors, and secondly, an integration of all its procedures (such as value analysis, process analysis, quality management and costing) into a single approach.

The book does still emphasize the dream of a system where business people can manage their proper processes without the need for IT intervention. The holy grail of zero coding promised by several of the BPMS suppliers in the market, but in my opinion still a pipedream. Much like VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet, let the business do its own data management, it ultimately boils down to teaching your business to code (for example write functions in the cells of said spreadsheet).

From the third chapter on, the book dives into the current state of affairs. The three parameters for market competition have been extended with a fourth. Where enterprise would compete by being first to market (“faster”), and offer products of superior quality (“better”) or being the price leader (“cheaper”), now another factor is superior service. Enterprises must aim for pleasing the customer. This can be captured in the following simple points:

- King customer is now a (very much informed) dictator, forcing enterprise to give him what he wants, when and where he wants it, and how he wants it, giving rise to just-in-time processes.

- Mass production is giving way to mass customization. Customization has become the new invisible hand of the market, so that in many cases the products are themselves processes.

- Customers are demanding total solutions. For example, a plane ticket does not equal a vacation. And so, processes will replace bundles.

- Industry boundaries are blurring. More and more enterprises seem to move to a conglomerate style, with many seemingly unrelated supply chains.

- Value chains are becoming a unit of competition. Process acquisition, aggregation and combination are quickly becoming the norm to insure the requested total solutions.

- Collaboration and coopetition are replacing the conventional forms of competition.

- Change has become the only certainty. I do wonder, even in 2002, was this such a revelation? Seems rather obvious now.

At this point we are treated to an attempt at defining what a business process is. A task I always find daunting, and looking at the Wikipedia page, it seems I’m not alone in this belief. But for this work, it comes to this:

Although it stipulates delivering customer value as a prime directive for a business process, at least further in the chapter we get to the supporting processes (which I guess implicitly deliver customer values). These processes include unique internal processes, industry best practices, and compliancy processes. Taking into account these types of processes makes the list of processes by company to quickly number in the hundreds. This confirms the need for rationalizing processes across divisional boundaries, exploiting synergies, and removing redundancies, but also renders it a costly affair, especially in such disrupting events as for example mergers.

However you might (or might not) automate, there are some things your business will always need/want:

- Describe and quantify services rendering by partners, so to measure and enforce service level agreements

- Allow specialist firms to handle part of the process, but retain control over the process as well as the ability to monitor them. Require these partners to demonstrate their proposed processes (or parts)

- Integrate services from partners into the processes with ease

- Expose internal capabilities as services for potential partners and customers

- Have to ability to outsource monitoring, measuring and optimizing processes to third parties

- Compare internal costs to costs of collaboration

- Custom business processes adapted to the local market conditions for competitive advantage (in contrast with globalization)

An entire subchapter is dedicated to all sorts of regulatory and best-practice industry frameworks, such as CPFR, TMFORUM, HIPAA… It brings these up as an introduction to the concept that, unless you automate your business processes, these regulatory compliancy needs are estimated to add up to 10 percent of any ERP implementation in such a market. This is exacerbated by the existence of legacy systems that encode business processes, and are sometimes even considered heritages, namely the source of the competitive advantage. In short, BPMS engines should address the entire spectrum of processes, as described in the table below.

| Simple, Static Processes | Complex, Dynamic Processes | |

| Core and Primary Activities (Strategic) |

|

|

| Context and Support Activities |

|

|

As the reader heads into the fourth chapter, the writers establish BPM forming out of an aggregation of all considerations and initiatives that came before (as described in the previous chapters). The first step towards BPM is to extract business processes from existing software, much like for example memory management was extracted from applications to the operating system. Architects will extract business rules from processes in an attempt to reduce complexity and to render them more maintainable. Process Management comes as a second logical step, relying on techniques as analysis, simulation, transformation and inspection to drive the process optimization effort. Third-wave BPM methods shift these efforts from merely IT people to a collaborative effort with business people. The management will shift from reactive to proactive dealing with change. However, unlike reengineering designs in the past, now these designs need to be directly executable and be capable of evolving with minimal impact on current business operations.

What is different from past efforts at BPM? The new BPM separates process design and subsequent process change from integration activities, which are to be managed in different cycles. These process designs are also directly reflected in the IT infrastructure and made tangible to employees through enterprise portals. Additionally, the system for this management has built-in metrics that provide that provide process-level instrumentation, in order to guide the optimization and refinement process.

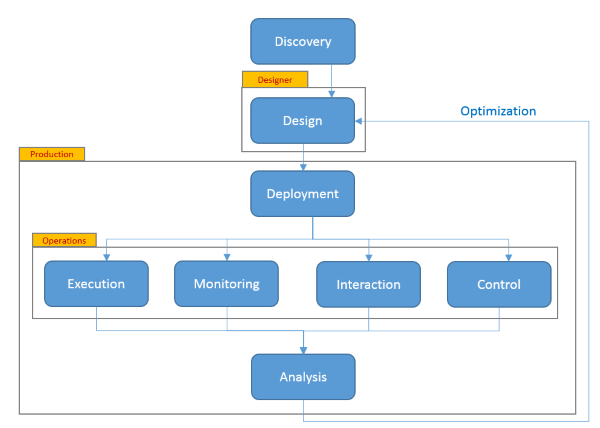

At this point, we are treated to the authors’ vision on the process life cycle. Most of the terms on this diagram are self-explanatory. For those less clear, here’s the explanation. Interaction means the use of process desktops and process portals to allow people to fully interact with the processes. Monitoring and Control applies to both process instances as to the system executing them. It includes the tasks (both technical and functional) needed to keep the processes running.

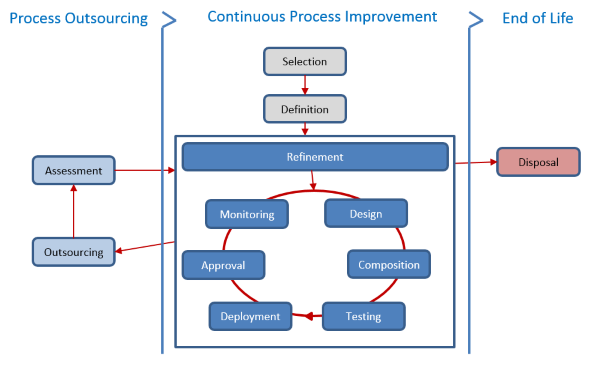

My own flavor of the lifecycle tends to include decision point for outsourcing and disposal in order to be complete. It however lacks the interaction part, but this could be added as an additional input for the refinement part of the lifecycle. Maybe I will add this in the next iteration of my lifecycle. I will need to give it some thought.

The book also reminds us that BPM is not only for large companies. Start-up businesses need to assemble a complete business infrastructure using a combination of off-the-shelf packages, components and processes. Such companies often defer process design decisions to the period before launch, and then rapidly evolve processes based on their first months’ experiences. Established organizations on the other hand face escalating technical integration costs because of monolithic legacy systems. Process management attempts to eradicate point-to-point integrations in order to let business processes drive application behavior and not vice versa.

BPM is also applicable to all business strategies. Customer-focused organizations can design totally customer-driven business processes from the inside out. Industry leaders have the ability to quickly respond to new business opportunities or unexpected competitive treats by preempting market shifts. This is an example of how to leverage the extreme agility offered by third-wave systems. Operationally efficient companies utilize process management to lower the total cost of process ownership, and at the same time, this management increases the possibilities for designing and deploying new processes.

The next chapter deals with the history of Business Process Reengineering. Championed by Michael Hammer in his Harvard Business Review article "Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate", the BPR approach to bring about radical change was not an easy task for the CEO’s, who saw it more as a methodology for fixing broken processes, or for tuning new processes that reacted to a new market and thus justified the significant cost. Additionally, it offers no method for developing these new processes or process variants, and no view on how to simulate new versions. After Hammer came Thomas Davenport with his work "Process Innovation". He introduced a view on BPR, which was more realistic than and not as black-and-white as the Hammer method, stating that continuous improvement may be preferable to BPR in certain scenarios. For example in relatively non-competitive settings or for processes where the basic business practices are not in question. According to him, radical change is to be reserved for responding to extreme competitive pressure.

Another sore point in BPR is that it does not incorporate how to tackle the management of processes. In an economically bad climate, organizations must focus on delivery and can’t invest in implementation of the newest trend in management theories, organizational structures or next generation software components. It needs processes that manage themselves through metrics and optimization structures. This can be achieved by veering from the need for sequencing and timing for new processes, and instead focusing on the interactions and relationships within processes, which aid tremendously in designing them.

The chapter on business process outsourcing (BPO) attempts to provide a possible answer to the conundrum of how to tackle reinvention of the organization without the painful reengineering path. As I show on my life cycle diagram, during the refinement part of a process, the question must be put forth: Can an organization simply acquire the best practice and best-in-class process it needs to leverage business transformation to the extent where it can radically redefine the organization? The author states that BPR is about restructuring selected processes while BPO is about restructuring the entire business. This may seem somewhat ambitious, but certainly possible. However, caveat emptor. The example of Sara Lee comes to mind. Here’s an organization that outsourced everything but its core business (being just the brand name), and streamlined itself into oblivion. The influence BPM in its third wave has on BPO is the ability to create a managed virtual enterprise.

By digitizing a process, it can be easily monitored, unplugged and outsourced. Every business category (ranging from strategic procurement to supporting processes like HR) can be a viable candidate for BPO. It is imperative in these cases that this digitization includes analysis, simulation and optimization of processes, as well as the ability to manipulate, combine and recombine the process. The BPO partner needs to allow for this as well. The process will be part of the intellectual property of the outsourcer, and proper knowledge management of the outsourcer will complement the process management of its customers, enabling them to make smarter and faster decisions. A complete management of the process lifecycle is crucial to control the changes made to it, and the metrics derived from these processes (instead of Service Level Agreements) become the basis for the contractual basis between the two. The downside of this approach is that the business processes associated with this type of value-chain integration come to depend on complex commercial and financial arrangements.

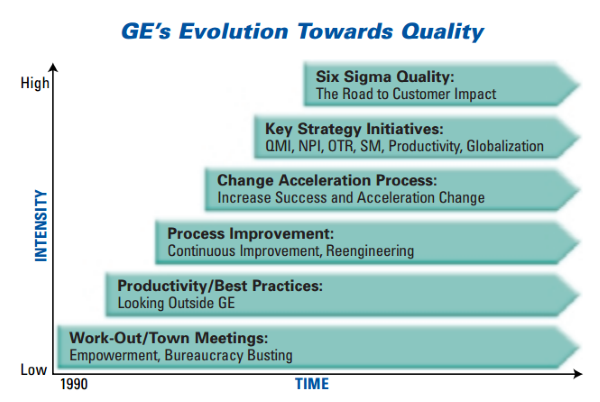

There are several ways to improve the business processes that govern an organization. One of the more known one is Six Sigma, and so this book goes into detail on how to marry its new vision on BPM with the quality improvement methodology. It shows the graph below, which is the General Electric Roadmap (available on their site) to demonstrate that there are big companies who have made Six Sigma part of their operational DNA. The chapter also branches out to how the third wave comes into the picture during the change management exercise inevitably linked to all process changes, promoting these exercises from a manual effort (easily spotted with the presence of handwritten change request, supported by documentation, submitted to document control, and form validation) to an automation of this process using BPMS solutions. This change management should take heed to couple the outcomes of process improvements back to the knowledge workers in order to ensure their learning, translating into an effective knowledge management. Such is the way to achieved the learning organization described by Peter Senge in his work "The Fifth Discipline".

The chapter wraps up process improvement with the notion of Return on Process Investment, indicating that BPM allows for parallel process improvement initiatives, and thus with processes in different stages of the process life cycle, to be calculated as an aggregate of following elements:

- Process Design to Production Time and Cost: the time and resources needed to bring a new version of a process into production.

- Process Design Coverage: The degree to which a process is capable of modeling and including all participants, be they humans, machines or systems. In short: the functional fit.

- Process Customization Level: the ability to create and the maintainability of a large set of process variants.

- Process Lifecycle Continuity How easily a process can be modified to meet new requirements within the confines of the BPM strategy on an enterprise level.

- Process Transaction Capability Level: How easily compensation and transactional aspects can be incorporated into the process.

- Process Value-Chain Coverage: The extent to which the process can be extended in order to include all participants in the value chain (such as for example the BPO partners of the previous chapter).

Theory is great, but how to put it in practice: The cornerstone of chapter eight: Implementing Business Process Management. The book states assimilation as the key principle for such initiatives. Introducing Business Process Management should not be a big bang event, but rather a framework for corporate evolution. It should be tackled as a sustained approach, minimizing impact on current operations, but still incrementally moving towards a new operational reality. Therefore, it is advisable to manage the processes and their subsequent optimizations and changes as a portfolio. In order to master the discipline, the practitioners should mature along the following stages:

- The innocent: The person who has never heard of or is only vaguely familiar with the term BPM. This person has no concept of the tradeoffs associated with the discipline.

- The BPM Aware: These people have a notion of the complexity of the discipline, and are actively seeking to increase their knowledge of methods and techniques within the discipline.

- The Apprentice: The high concepts of BPM are known. The person cannot yet work independently on a BPM initiative, but can assist such efforts in an effective manner.

- The Practitioner: Ready to use BPM, this person can take process-engineering decision without relying on others, but mistakes are still made and count as a teaching experience. Concepts such as the organizational implications, deep integration of BPM in existing methodologies such as Six Sigma, the need for training and tool support, the industry data and collaboration standardization needs, and value chain benefits are gaining importance in his insights.

- The Journeyman: This person is mature in his knowledge of the discipline and uses it naturally and automatically, no longer absorbing knowledge from a mentor, but rather through a self-managed learning program.

- The Master: Has internalized BPM and knows when to veer from standards set out by the discipline, guided by a profound methodological foundation.

- The Expert: Thought leaders in the discipline, publishing works and giving seminars on the topics associated with the BPM discipline.

The final chapter is a summary of all concepts brought up in this book in the form of a fictitious interview. The question and answer style try to put a bit of a comical relief to a book brimming with conceptual musings about BPM. After a short epilogue, we still have a few appendix chapters to go for those related topics that the authors didn’t go too deep into detail about.

The first appendix is about the process language, pointing out the difference between BPMN and BPML needed for the difference in perception between the different stakeholders in the process life cycle. It also emphasizes the logical synergies between BPM and Service Oriented Architectures. The second appendix is an introduction to BPMS tooling, elaborating on a Model, Deploy, Manage model to work with this tooling in order to master its potential to the fullest within the organization, even making a detour to the Business Process Query Language as a management interface for process-aware applications.

The final appendix goes into the theoretical foundations of Business Process Management, where we distinguish the different characteristics of a process:

Wrapping this book review up with the notion that I now need to read its spiritual successor in the form of "Business Process Management: The Next Wave" in order to see how the writers' insights have grown over the last few years, and which of their theories have stood the test of time with their own experiences in the field.

| Review | BPM |