Economics of Money and Banking, Part Two (week 1)15th of October 2015 |

|

The last time I followed a course with Coursera already dates back to May of 2015, so I figured it was time to up my game again. The course that caught my eye was this one. Not the first part in the series, but since I already followed professor Schiller course on Financial Markets, and this course was about to start, I just went for it, hoping professor Schiller's course would be enough of a basis to build upon with this course. Given by professor Perry G. Mehrling of Columbia University, it aims to be a course on the constructions around money and currency in modern times, spread over 6 weeks and 11 lectures. For more information on these topics, the professor mentions this site.

One of the prerequisites of this course is knowing the difference between solvency and liquidity. So, as a recap, here's the difference explained. Solvency and liquidity are both terms that refer to an enterprise's state of financial health, but with some notable differences. Solvency refers to an enterprise's capacity to meet its long-term financial commitments. Liquidity refers to an enterprise's ability to pay short-term obligations; the term also refers to its capability to sell assets quickly to raise cash. A solvent company is one that owns more than it owes; in other words, it has a positive net worth and a manageable debt load. On the other hand, a company with adequate liquidity may have enough cash available to pay its bills, but it may be heading for financial disaster down the road.

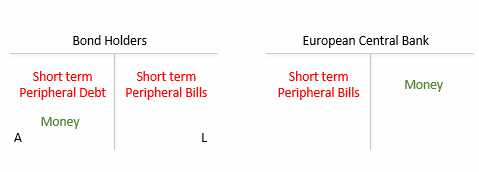

Applying the concepts of solvency and liquidity to current events, the course also put into perspective the Euro crisis of 2015 and examines the actions taken by the different participants (such as Mario Draghi of the ECB), in particular the reasons behind the actions and the result the participants hope to produce with them. The professor uses rudimentary balance sheets to show the trade-offs between assets and liabilities for each of the participants, as shown in the illustration below. The debt of the peripheral countries in the EU could be bought for money (both assets of the bondholders), which is bought as an asset by the ECB, that will then print additional currency as a liability to finance this. This type of balance sheet will be a recurring instrument for illustration in the course.

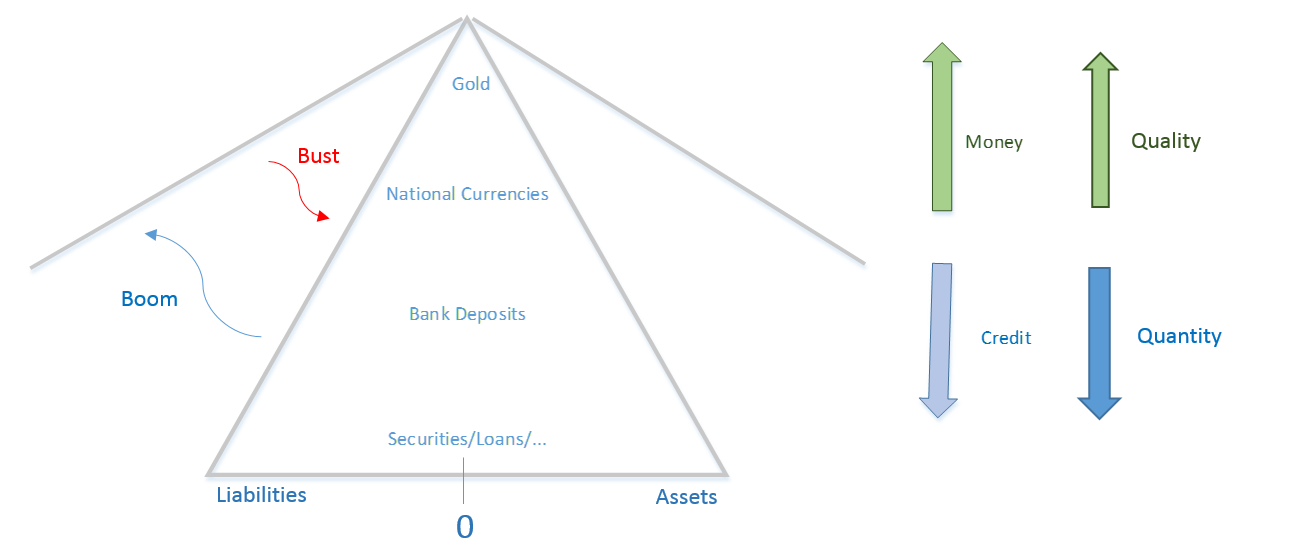

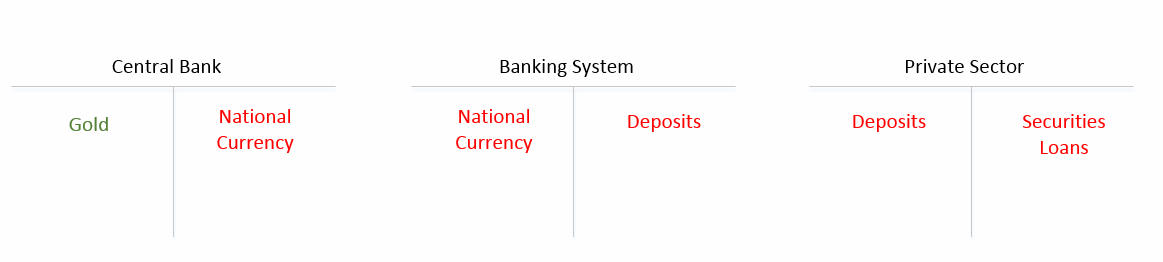

The other main structure the course will elaborate on is the hierarchy of financial instruments, and subsequently of financial institutions, wielding these instruments in their balance sheets. The illustration below sketches this hierarchy in an abstract manner. In the real world, there are more layers than these. But basically, the top is the actual money, being for example gold (in a gold standard economy) or some form of international currency. All steps afterwards are credit of some sorts, a promise to pay out in the layer above it. For example, a bank deposit is a promise to pay out in national currency at some point.

Here we see that money versus credit is dependent on the context. For national banks, national currency is considered money, while deposits are considered credit, but for a customer of said bank, he will consider the deposit money. To get a clear picture of the absolute division of these concepts, we look at the concepts of outside money and inside money, as formulated by Gurley and Shaw in their 1960’s book "Money in a Theory of Finance". Outside money is an asset that is not present on any balance sheet as a liability, and Inside Money is any form of credit. To verify this against our hierarchy, we draw the balance sheets, seeing that indeed only gold is an outside money, and thus no credit.

And to be able to have a thriving economy, these institutions also need to act as market makers, freely interchanging their assets and liabilities, based on an exchange rate (which for the banking system is the par: 1-for-1 ratio). The hierarchy also shows a dynamism in the market where the ratio money versus credit changes over time through booms in periods of irrational exuberance, and more credit is created, and periods of bust, where credit disappears, and we experience a financial crisis. These cycles of boom and bust are governed by two principles: Scarcity of (ultimate) Money [currency principle] and Elasticity of (derivative) Credit [banking principle]. You have schools of thought based on either such as monetarism or metallism for the former, and Keynesianism or chartalism for the latter. None of these schools have the ultimate truth, but contains a part of the whole. This part varies in size depending on where we find ourselves in such a cycle.

Economics of Money and Banking, Part Two (week 2)10th of November 2015 |

|

The second week of the MOOC focuses more on international currency exchange and the mechanisms associated with this. In order to create a solid base of understanding the money view of both Chartalism and metallism are examined and compared to each other, so that both views can be mapped onto this foreign currency exchange.

The main difference between the two views is evidently the backing of national currency. Where Chartalism (as posited by economist Georg Friedrich Knapp in his seminal work “State Theory of Money”) dictates that national currency be determined by fiat of the sovereign state (or taxing authority), Metallism links the currency to a backing of precious metals. The former, as described in the first week summary, subscribes to the Elasticity of (derivative) Credit, while the latter adheres to the Scarcity of (ultimate) Money.

As indicated, Chartalism thinks of money as a creation of the state (or taxing authority). It is given value through the power of said state to levy taxes payable in this currency, and ultimately, its power to enforce these taxes. This gives the state an easy way of financing its endeavors through operations on the value of the coin (such as for example a depreciation to reduce domestic debt).

Metallism has its exchange rate linked to the ratio of the coin in precious metals (such as gold or silver) or in other words a mint par ratio. The reasons for introducing currency, and not simply paying in gold lies with the fact that distribution costs money as well, so instead, the gold stays put, and the arbitrage of the trade transactions will be done in gold points. The spot rate (the price quoted for immediate settlement on a commodity, a security or a currency) will become equal to the forward interest rate.

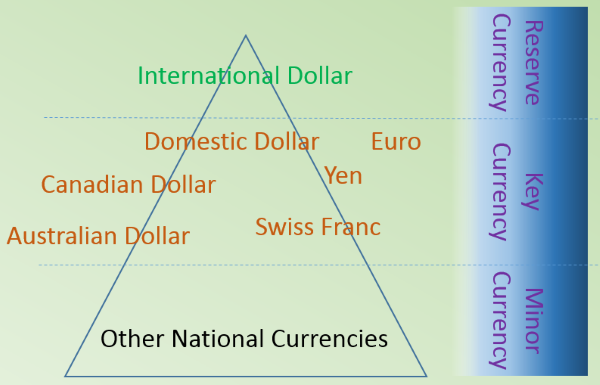

When executing a foreign currency exchange, an exchange rate needs to be determined. In order to do this, a unit of measure is needed to compare both coins. This is called the Reserve Currency, and is the International Dollar. Since almost 85% of all foreign exchange transactions are from or towards the Domestic Dollar (or US currency), the International Dollar is kept par with the Domestic Dollar. A level under the Reserve Currency we find the Key Currencies (or Majors). These are the principal players in foreign exchange. For example, the foreign exchange transactions where one of the legs is a major currency (apart from the dollar) make up 51% of all trade. A third level are the Minor Currencies. These are not traded against each other, but transactions where one of the legs is first traded towards the Dollar.

There are different approaches on how to look at the value of money, such as for example the Quantitative Theory of Money (advocated by Metallism) and the Purchasing Power Parity (advocated by Chartalism). Both are fundamental theories within the field of monetary economics. The Quantitative Theory of Money states that money supply has a direct, proportional relationship with the price level. Or to put it in a formula:

In this formula, the following abbrevations are used:

M: Quantity of Money (the amount of money in circulation for a certain period)

V: transactions Velocity of Money (average frequency across all transactions)

P: Price Level

T: aggregate Transactions

Rather straightforward, the more money is printed, the lower the value becomes. One of the main opponents of this theory is John Maynard Gaines, stating that monetary value is not strictly determined by its supply in his work "The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money".

The Purchasing Power Parity Theory links the exchange rate of currency (and thus its value) to the relative price of goods in each respective country. This approach is useful, but has several issues associated with it. Since the price levels of goods only vary over longer periods, this is invariably a long term view of the value of money. It also makes abstraction of such concepts as interest levels. Again a fairly straightforward, its formula is this:

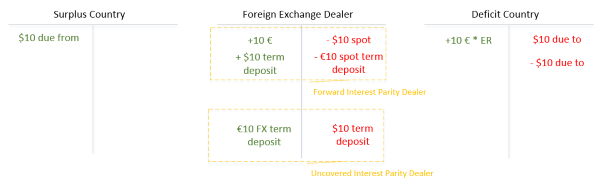

While both of these theories have a view on part of the truth, either by associating exchange rate to goods (PPP) or assets (QTM), they both make abstraction of liquidity. This is regarded more in the money view, where there is a comparison of money in terms of money, offering another part of the truth. In order to make this possible, foreign exchange dealers are needed, freely exchanging one for the other, and to hedge their own risk for the exchange (which is a speculation of futures, so a forward rate) by also acting as a forward interest parity dealer.

When acting as a forward interest parity dealer, they in effect act as a matched-book dealer that transfers the risk of the speculative interest rate to the speculative dealer by issuing term deposits. Thus their outside spread is determined by the Covered Interest Parity. This is only viable if there is movement in the interest rates of the foreign currency (in this case €) so that the term rate can go up. This is determined by the Central Banks of the deficit country as this term rate is closely linked to their overnight rate.

The uncovered interest parity dealer acts as a speculative dealer, and is exposed to the price risk. However, he intends to gain profit by the difference in expected spot rate and the locked in future spot rate he is willing to accept.

These foreign exchange dealers are also a very good example of hybridity, where the lines between the government banks and private banks tend to blur through mutually beneficial interactions. This could in the past be seen in war finance, where the treasury bills issued by the government were accepted as money by the private banks, and the government legitimizes the deposits created by private banks as state currency.

The week’s lecture ends with an analysis of the article "A Reconsideration of the Twentieth Century" by Robert Mundell (Nobel Prize winner and one of the fathers of the Euro), which divides this century into 4 acts.

Act 1 runs from 1900 up to 1933, and is called the "Confrontation of the Federal Reserve with the Gold Standard". In this period, the First World War causes the gold standard to only remain for the US currency, and after its conclusion the recoupling of the gold standard to each of the other domestic currencies. This recoupling significantly increases the scarcity of gold, and at the same time deflationary pressure. The US Federal reserve in an attempt to hold on to the gold – dollar mint par, increases interest rates in a depression, and this in term leads to a worldwide depression (1931), and the gold standard collapses.

The second act (1934-1971) sees a confrontation between national macro-economic management and the international fixed exchange rate. The domestic central banks want to play with their interest rates, but are hampered by these fixed rates on the international markets. Solutions are sought, with for example John Maynard Keynes suggesting his Bancor Proposition, where Bancor becomes the true global currency instead of gold, and countries trade using this. This would introduce elasticity as additional Bancor currency is created when needed. The US opposed this plan, and put forth the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which used Special Drawing Rights (SDR) in trade transactions for each member country, backed by domestic currency. However, SDR per country was fixed, and such the discipline is honored. This causes the US to leave the gold standard, and the end of fixed exchange rates.

A third act (1972-1999) is the period of stagflation, or a period where inflation coincides with a period of increased unemployment. Flexible exchange rates introduce too much elasticity in the international markets, with domestic currencies fluctuating wildly and a severe lack of international discipline. The introduction of the central bank discipline in an attempt of each country to stabilize its price fluctuations should in extension stabilize exchange rates. However, speculative foreign exchange dealers still cause the rates remain very volatile. The end of this act is marked by the introduction of the Euro.

A final act (2000+), no longer part of the twentieth century, is the global financial crisis, where there is a run on US Treasury Bills favored about the Residential Mortgage Based Securities). Especially those securities not under US control (such as those counted as assets in European banks) return to US soil in large droves. This is what we call home bias, and is an adverse reaction to the globalization of the previous period.

Economics of Money and Banking, Part Two (week 3)12 of June 2016 |

|

The third week focuses on the role of the central bank in international change, more specifically the evolution from gold standard times with the Bank of England, as well as the subsequent roles of the foreign exchange dealers under this regime. Starting position for the evolution is a time where the pound sterling notes of the Bank of England were accepted as the true international currency and they were kept on par with gold. These lectures are positioned on the financial world stage circa 1873.

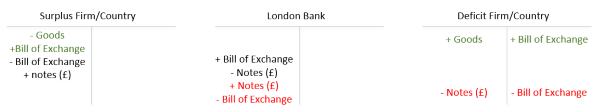

Much as nowadays most international exchanges happen by using the Dollar as intermediary, at this point in history, the £ Sterling fulfilled this function. The trade between an non-UK surplus firm or country and a non-UK deficit firm or country happened by settling a bill of exchange with a bank within the city of London.

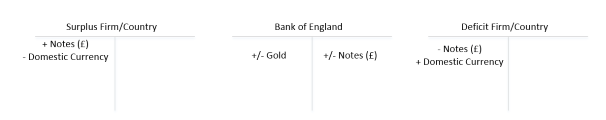

The main issue with this is that these countries/firms are not using the £ Sterling notes domestically, so for things such as worker wages, domestic currency is needed. In order the switch the notes to this domestic currency, once again London (or more specifically the Bank of England) plays the role of foreign exchange dealer. This firmly seats the Bank of England at the top of the monetary hierarchy.

The viability of the dealer model in this instance is enabled by the inner and outer spread of the exchange rate (price space in gold points), derived from the transport cost of gold (δ). Take the example of dollar versus pound under

consideration:

£ = y ounces of gold

Exchange Rate = £ / $ = x / y

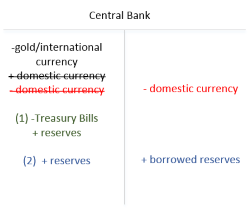

When the Central Bank of a non-UK country would start its market dealing, it runs into the issue that its assets (gold and international currency) are limited. And by transferring them to domestic currency, this domestic currency becomes a liability, and effectively contractionary monetary policy starts to emerge. Unlike private banks, the Central Bank has several mechanisms it can use to counteract this phenomenon. The most logical course of action is to sell treasury bills to replenish its reserves. Note that this drives the price of these bills down as a consequence. A second option is to borrow reserves (gold/international currency) from the Bank of England. If a private bank would employ this second action, it would get domestic currency from the Central Bank and thus there would be no difference between reserves and domestic currency on the assets sheet.

The private banks in such a system cannot play on the price space, but rather act on the interest space. These banks take on liquidity risk with its transactions. They are lending long term and borrowing short term, and mitigate this liquidity risk through manipulation of their discount rate with an outer spread determined by the quote of the Bank of England. The Bank of England will in effect be the Lender of Last Resort in this system. As such the lower limit will be the market interest rate and the upper limit will be the guaranteed bank interest rate. However, this presents the possibility of both an internal and an external drain (parties exchanging their notes for gold). The internal drain can easily be fixed by offering deposits instead of gold. The external drain necessitates additional reserves. The Bank of England does have some mechanisms that Central Banks do not. They can raise the bank rate, making the renewal of notes more expensive, so that there is an influx of gold. The most drastic approach is to suspend payment in gold, effectively turning the system into a pure credit system.

In case the Bank of England switches to a credit system, there is a consequence in that the entire foreign exchange system as elaborated earlier, ceases to work. It also forces a depreciation of the Pound Sterling against gold, but not necessarily against other currencies, as it still remains the best possible currency to use in such a system. However, moving away from a gold standard, the spreads for the Central Banks (both in price and interest space) disappear as the backstop for exchange disappears. And the abolishment of such a system was strongly advocated by John Maynard Keynes in his book “A Tract on Monetary Reform” in 1923, and he states that the war finance had already de facto turned the world away from the metallic way of working.

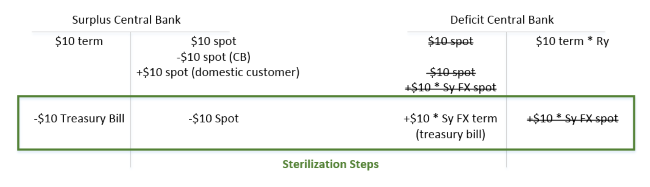

Central Banks can also act as foreign exchange dealers when need be, becoming the Dealer of Last Resort. The reason the Central Banks might perform this task is to insure the liquidity of their domestic market when the domestic market does not offer enough profit for private dealers to take the liquidity risk. This is to protect the domestic customer from price gauging and to promote the efficiency of the foreign trade. If there is not enough liquidity, this reflects poorly on the economic reputation of the country, directly concerning their Central Banks. It does in effect mean the Central Bank of the deficit country becomes a speculative dealer because of the needed sterilization steps it must take, exchanging $10 times the interest spot rate (Sy) against $10 times the interest term rate. The market interest rate is shown in the balance sheets below as Ry.

The concept of manipulating these spreads exists till this day, and is for example one of the measures taken to curb High Frequency Trading or "Cyborg Trading", where computers use algorithms to calculate at lightning speeds which transactions to execute in order to turn a profit, at the expense of human traders. This will cause them to dial back their trading and cause a drop in liquidity. In reaction, a lot of trading platforms have introduced a wider spread of pricing (such as fixing a decimal of the points to either 5 or 0). An interesting TED Talk by Kevin Slavin, titled “How Algorithms Shape Our World” explains the basic concepts behind these algorithms for those interested.

Economics of Money and Banking, Part Two (week 4)25th of July 2016 |

|

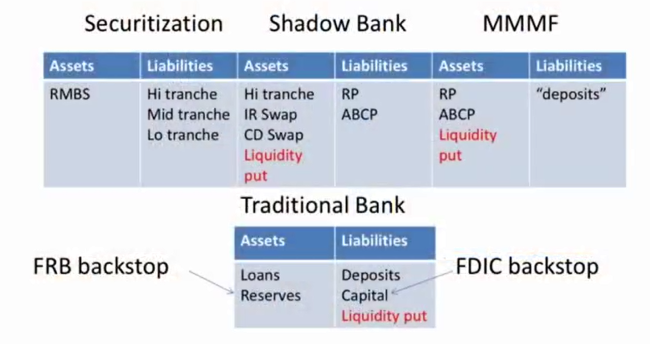

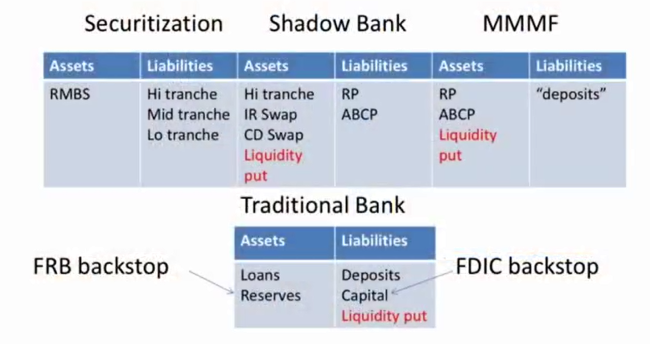

This week’s lectures are all about putting into perspective the phenomenon of shadow banking and its relationship to the workings of the Central banks. Shadow banking boils down to the money market funding of the capital market lending. So, instead of backing deposits (liabilities) with loans (assets) as is done by a traditional bank with the Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as backstops, there are several hedges in between the Residential Mortgage Based Securities (RMBS) and the deposits made in the Money Market Mutual Funds (MMMF). This is through a system of Interest Rate (IR) Swaps, Credit Default (CD) Swaps, Repurchase Agreements (RP) and Asset Based Commercial Paper (ABCP).

Since no backstops exist in shadow banking, there is an inherent liquidity risk. The solvency risk is mitigated as it is the CD Swap and IR Swap holders that carry this risk. Liquidity risks usually roll over into the parent bank, and as such become a liability of traditional banks, and by consequence of the government in its role as backstop.

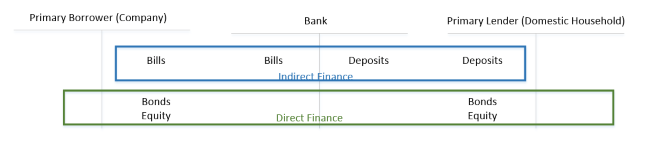

The lines between capital markets and financial markets become blurred through this shadow banking. And it is worth noting that the difference between the two markets is mostly academic (capital market theory is taught in finance classes, while money market theory is taught in economics classes). However, at the time of the gold standard, this distinction was more than just academic. There was a strict separation between the short term finance (or indirect finance) of the money market and the long term finance (or direct finance) of the capital market. The definitions of direct and indirect finance were introduced in “Money in Theory of Finance” by John G. Gurley and E.S. Shaw in 1960.

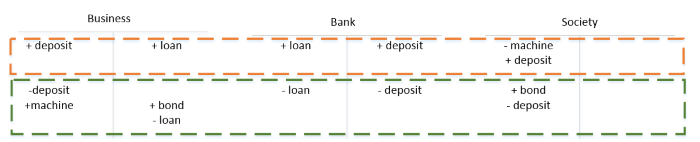

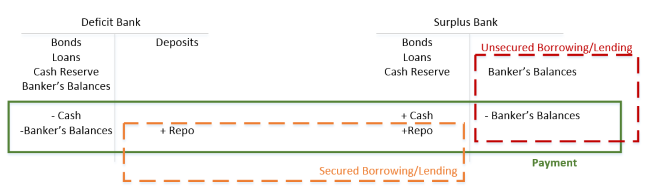

At some point however, direct and indirect finance get intertwined, as for example a business might want to buy a machine, taking out a loan to finance it (Money Market Payment [orange dotted rectangle]), and afterwards convert this loan into bonds to secure a more permanent way of funding (Capital Market Funding [green dotted rectangle]). Here the loan serves as an intermediary (using the elasticity of the market) to get the ball rolling.

In the world of 1873, before the introduction of the Central Bank in the United States, there was another form of shadow banking, as long term finance was needed due to the fact that the US was a developing country in need of a large influx of resources to develop for instance its infrastructure (railroads and the like). In this lack of a Central Bank, the rating companies (such as Moodies) emerged to perform the task of credit analysis as surplus banks don’t want to do this for each of their borrowers and their collateral portfolio. And the type of liquidity needed was the shiftability of the bonds being issued. This is what the Central Bank later on would start to backstop.

This was also the idefix of Joseph Schumpeter, who emphasized the importance of banking for economic long term development, citing banks should be willing to expand their balance sheets (through for example bonds) to stimulate this, leading to the money market funding the capital market lending (enter shadow banking). Another economist of this same persuasion would be Henry Dunning Macleod. However, such a system would have to be disciplined to curb this creation of money.

These expansions of the balance sheets (in the form of deposits) are largely permanent funding, as households consider these deposits not only as a payment method, but also as an asset. The bank only needs to retain a fraction (~10%) of its deposits in cash to buffer for the fluctuations in the deposits. And so banks are enabled to do long term funding. It becomes cheap funding for all stakeholders: house mortgages, loans, treasury bills…

You need intermediaries to make indirect finance work, and aside from the banks, there are other parties willing to expand their balance sheets so that the mismatch of the liabilities businesses offer and the assets households want, is met. Typically these are pension funds that take pension benefit promises as liabilities to equities as assets, and insurance companies that take bonds as assets to cover their insurance policies as liability, once again denoting the shiftability of bonds and equities to allow for such a system. However, the main issue with this type of funding is the risk of the assets which some party needs to absorb.

Because of this risk, the evolution in the US has been to move closer to direct finance in employing Bond Mutual Funds. Here the risk is passed through to the households through shares as liabilities for risky equities (Stock Mutuals) or bonds (Bond Mutuals). The previously mentioned mismatch is addressed through price drops and rises of the risky assets until they match the assets wanted.

Coming back to Futures (see week 2), they are financial contracts between parties to trade a quantity of an asset for a price agreed upon at the moment of the contract (forward price) followed by a delivery and payment on a future delivery date. This is “Banking as Advance Clearing”. These changed expectations/views on the future state of a business can and will have consequences on the present day cash flow, and will impact the survival constraint of a business. The main difference with Forwards is the cash flow.

For Futures there is a constant cash flow (introduced by swaps), whereas Forwards only cause cash flow one (at settlement). These swaps are determined by the value of the Forwards contract, which fluctuates over time (converging towards the eventual actual spot rate), and this value is determined by the spot rate at the time of evaluation minus the delivery price set in the contract.

Forwards can be hedged by different stakeholders: Either by another firm that is willing to lend against the set forward rate (with the bank as intermediary). The banking system can hedge its forwards between banks using the Forward Rate Agreement, or private dealers can be used via the Futures Exchange where the spread is the different between the forward rate and the futures rate (and ultimately the expected rate in the spot money market).

The Futures and Forwards market leads to what is known as Cash & Carry Arbitrage. When matching a Forwards Contract with short term assets (such as for example a part Repo and a part Futures), financial intuition would suggest there is no room for arbitrage, since both parts of the equation should be equal in value. However, since the cash flows in Futures are recurring at small intervals, and they are expected to create negative cash flow leading up to the positive payout, there enters a liquidity risk. This makes the arbitrage play on the spread between the borrowing at the actual interest rate and lending at the expected rate.

Economics of Money and Banking, Part Two (week 5)5th of November 2016 |

|

The lectures of week 5 focus on swaps. After recently seeing the 2015 movie “The Big Short” about how the world economy came crashing down because of worthless assets held by all banks, and how swaps were used to profit of this by certain individuals, the topic really spoke to me and I wanted to know more. Although the movie talks a lot about credit default swaps, the professor deep dives into the interest rate swap market.

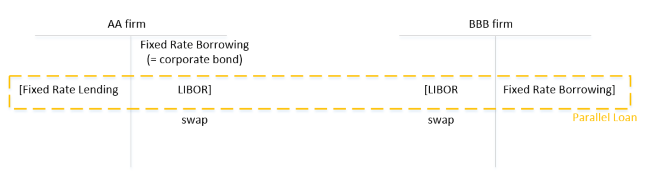

Explaining a swap, the lecture talks about an example between a AA-firm and a BBB-firm. The main reason the possibility for a swap arises is because of inequities in the market. AA-firms can borrow at lower rates than BBB-firms, both in the term loan floating market, as well as in the Fixed Rate Market. However, in the term loan floating market (London Interbank Offered Rate or LIBOR), the difference is so small that the BBB-firm actually gets a comparative advantage.

The balance sheet for this transaction is quite basic, where fixed rate loans by the AA-company are swapped against floating term loans of the BBB-company, and only the net difference is paid. This results in the balance sheet looking like this:

The example given by the professor reads with the following interest rates:

| Term Loan (Floating) | 5y Fixed Rate (Eurobond) | |

| BBB firm | 6m LIBOR +1/4 | 5.85% |

| AA firm | 6m LIBOR +1/8 | 5.375% |

| Difference | 0.125 or 12.5 basis points | 0.475 or 47.5 basis points |

The difference between these basis points is 35 basis points and this is the spread the swaps will operate with, dividing this spread between both parties. The idea is that the BBB firm hedges itself interest rate shifts by swapping financing its LIBOR with the fixed loan rate of the AA firm. This loan is at 5.375%. Add to this the interest rate of the LIBOR (=1/4), you get a fixed rate of 5.75%. This is still 10 basis point under their own fixed rate. The LIBOR rate of the AA firm will be leveraged by the -1/8 swap being paid by the BBB-firm, giving a net profit of 2/8 (or 25 basis points). The only risk for the AA-firm is that the credit rating of the BBB-firm changes, making their LIBOR more expensive and ending the swap, and defaulting the payment back to +1/8.

Because of this 35 base point spread, there is also an incentive for dealers (usually in the form of investment banks) to become involved. Since the AA-company is exposed to the movement in credit rating of the BBB-company, which is up for renewal each 6 months, the introduction of a dealer shifts that exposure towards the portfolio of said dealer. In addition to this, the matching of the swaps no longer is a concern of either company, as was the case with the dealers in the foreign exchange market. And these swaps happen at all maturity levels, causing most of the liquidity in the market, as swaps are basically IOU’s being passed along and exchanged.

This system was already envisioned by Fischer Black in 1970 when he stated that a risk free security should be comprised of a risky security (corporate bond), an insurance/hedge (interest rate swap) and a credit hedge (or credit default swap).

The maturation of the Euro currency shows these two tenets of shadow banking very well. During the Euro crisis of 2015 it became clear that for example in Italy it became increasingly more difficult for small and medium sized enterprises to get loans. The banks that traditionally hedged this with treasury bonds were re-evaluating how to raise capital, and the corporate world turned to shadow banking, having lost faith in banks to provide syndicated loans, and instead issuing massive amounts of corporate bonds to get their liquidity. Not only was the capital market involved, but also the money market moved to shadow banking, as up to 40% of all Euro currency trades happen in London (which is outside of the Euro zone). These two market tendencies form the basis of any shadow banking system.

Credit Default swaps are in principle not that different from Interest Rate Swaps. Suppose a party has a risky corporate bond, they would want to hedge this with a treasury bond of lesser risk (being a CD swap). In essence they would want to limit their credit risk of the corporate bond in time. You could conceive them also hedging this treasury bond with treasure bills (being an IR swap) to be long on fixed rate and short on floating rate. Similar to an insurance, you pay a premium each month the corporate bond pays up, and when it doesn’t you get the difference between the face value of the bond and the price at the period of the default paid out. It is similar, but not an actual insurance, because it isn’t regulated as an insurance. Issuing a CD swap is synonymous to gaining exposure to the credit risks of a bond.

To have a market dealer in the middle to sell these CD swaps, it needs to be able to hedge these. Individually, these will not be very attractive for some asset manager to take them into his balance sheet, but when grouped together to form a portfolio, this becomes a way for an asset manager to get into the corporate bond market. The pricing of such portfolios happens through the Credit Default swap index (CDX) for North American and Emerging Market companies, and iTraxx for the rest of the world.

A corporate bond is a debt security issued by a corporation and sold to investors. Basically, corporate bonds are pledges from a company to pay out a periodical interest (in the form of coupons) over a stated term as well as the principal sum (face value) at the end of the term. The value (pricing) of such is bond is therefore determined by the interest rate governing the coupon, as well as the rating (BB, CCC …) given to the bond. Since there is a higher risk attached, naturally these bonds would have a higher interest rate than treasury bonds.

A few examples now of where shadow banking got the system into trouble: These are the case of UBS (a Swiss bank), Goldman Sachs (a US bank), and of course the 2008 housing market bubble:

UBS lost a lot of money by doing what it considered a Negative Basis Trade. It was forced by their regulator to write up a report afterwards on how they lost so much money. This report can be found here. When they noticed that the spread of AAA CDO tranches (mortgage backed) was always greater than the insurance cost issued by AIG (in the form of credit default swaps), they booked a guaranteed profit for the next 20 years in the year of purchase, and used this to do money market funding (repo, ABCP…). In theory there was no risk, however due to small fluctuations in the value of these traunches, it could not roll over their funding and was forced to sell the original collateral, dropping the value even more, and setting of a spiral. In fact, there was a definite risk, but it was a liquidity risk. It is a textbook example of shadow banking where money market funding is done through capital market borrowing.

The interaction between Goldman Sachs and AIG in 2008 led to monumental losses for the world’s leading insurance company. Goldman Sachs was playing market dealer for Credit Default Swaps for its clients by buying them from AIG on the condition that a change in credit rating of AIG would result in them paying out the value fluctuations of said Credit Default Swaps. As AIG didn’t perceive any risk, these CD swaps were being issued almost without reserve. It led to a 30 billion dollar payout to Goldman Sachs when the credit rating of AIG went down, making the insurance company insolvent.

Coming back to the movie, or the events on which the movie was based, John Paulson foresaw the bursting of the housing market bubble and wanted to expose himself to the credit risk by buying CD swaps on these Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS). He approached Goldman Sachs, who set up a company called Abacus, that sold Paulson these CD swaps and hedged them by packaging them in a Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) tranche and selling these tranches to IKB as an asset. Having gotten the money upfront in this fashion, that money was used to buy risk free treasury bills in order to guarantee that when and if the market would go belly up (reducing the CDO to zero value) they payout to Paulson would not be a problem. This is basically a synthetic CDO, as assets are sold based on the mortgages not owned by Goldman Sachs. Essentially, this is a side bet on existing RMBS assets.

Economics of Money and Banking, Part Two (week 6)14th of December 2016 |

|

The final week delves into the relationship of shadow banking with regulation and the overall economic reality. Where traditional banking is usually regulated by forcing a segment of their assets to be long term (bonds, equity…) in order to reduce exposure to liquidity risk, shadow banking sidesteps these regulations by its very nature. Although it might seem that it is still backing loans with deposits (see the illustration from week 4 repeated below), there are numerous layers/levels in between, as shown in the illustration Sultan Pozsar made for the New York Federal reserve. The main difference, as stipulated in week 4, still remains the lack of government backstops. Regulation proposals have already included more prize transparency on Over-The-Counter (OTC) derivatives and insurances on adequate collateral and/or margins.

To say that the shadow banking system had no backstops is incorrect. When setting up the system, banks introduced a private (and immature) backstop with their parent (traditional) banks. They, either through contract or reputation, put up a liquidity backstop as a liability in their balance sheets. However, this only works when the parent bank remains healthy. If not, this rolls over to a failure of a traditional bank, which then taps the government backstop in place for such banks. So, indirectly, the government had also become backstop for the shadow banking system. There was also a private solvency backstop in the form of the Credit Default Swaps placed against the tranches of different levels of risk. However, this used a mature global funding system already in place for foreign exchange, but passed an immature product into this system (being the CD swaps), and this attempt to transfer the risk ultimately failed as well, leading to the global crisis of 2008.

The evolution towards shadow banking largely came from two distinct forces in the world of finance. On the one hand the financial globalization and securitization, made possible by the grouping of loans in order to get the needed scale to transfer these assets on an international scale, on the other hand the evolutions in the capital market interaction with the money/derivative markets, making it possible to easily shift risk around and allow for pricing of these derivatives, allowing for any melange of risk exposure an interesting party would want.

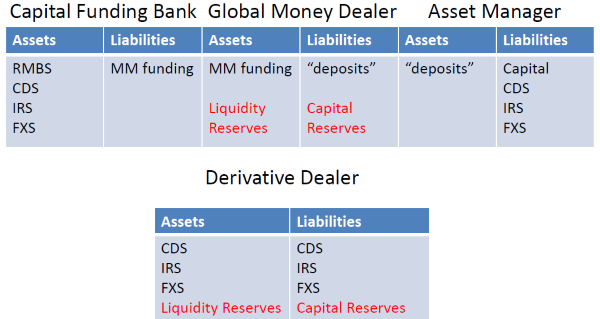

Moving away from the negative connotation of the word “shadow”, a more accurate description would be a Capital Funding Bank (CFB). In between the CFB and the Asset Manager will be placed a Global Money Dealer which is swapping out the Money Market Funding for deposits. In an ideal world where the dealer is a perfect matched book dealer, the risk is transferred completely, and the only capital is on the books of the Asset Manager. Wanting to enforce regulations made for a Jimmy Stewart bank on this structure would be counterproductive and fraud-inducing. It needs its proper regulations mapped on their financial reality.

In order to secure a mature backstop for these two types of dealers, a Central Bank (or consortium of Central Banks) is needed, backstopping the liquidity (through liquidity puts) of the dealers through CD swaps, IR swaps and Overnight Index Swaps. Looking at the actions the Federal Reserve took in the shadow banking crisis of 2008, it became a dealer of last resort with these actions on its balance sheet, and in fact acting like a Central Bank.

When we look at the concept of Inherent Instability of Credit, coined by Ralph Hawtrey around 1930, the boom & bust cycle is not solely related to shadow banking, but has always been there, hence a need to manage this. Looking at the Treynor model for market makers, whenever the equilibrium between asset manager and capital funding bank partners is disturbed, the market maker will try to absorb this by changing the price according to supply and demand (reflected on the inside/outside spread). And the ultimate outside spread for a shadow banking system is as described in the previous paragraph the Central Bank.

In order to create a sort of private mechanism for dealing with the issue of value fluctuations in collateral, new collateral flows for shadow banking needs to be put in place. Remember the survival constraint: Liquidity kills you quick. The money lending of a capital funding bank can have a collateral of for example RMBS, translated into capital deposits on the balance sheet of the Asset Manager, which takes care of his solvency. However this does nothing for the liquidity risk involved with the value fluctuation of said collateral, which in term will reflect on the balance sheets of derivative dealers. Here the collateral should be adapted to the new situation (for example through rehypothecation) in order to form a sort of private backstop. This is needed for the Central Bank to become a Last Resort, and not a mechanism to be called upon daily.

In order for the Central Bank not having to act each day, the robustness of the dealers should be priority: For Matched Book Dealers, there should be liquidity reserves on the balance sheets, and for speculative dealers there should be capital reserves. This gives us 4 key principles to hold up:

- Key players in market-based credit system are dealers, not shadow banks per se.

- Key backstop for matched book dealers is liquidity, not capital.

- Key backstop for speculative dealers is capital, not liquidity.

- Survival constraint is about collateral flows, not just payment flows.

In essence a dealer provides the relaxation of the survival constraint of companies through selective control over liquidity allocation (matching cash inflows to cash outflows). It does this by selling exposure (to liquidity risk) on their balance sheet. They bridge the gap between a needed cash outflow of a company to a lacking cash inflow or vice versa though borrowing and lending.

This leads to the three views on the world of banking, namely the money view, the economics view and the finance view. The money view can be described as “the present determines the present”. What is important is the interaction between the cash outflows (governed by discipline) and the cash inflows (governed by elasticity). Next to that, we have the economics view (or “the past determines the present”), where we state that capital depends on the investments leading up to the present. Finally, we have the finance view (or “the future determines the present”) where capital (or the pricing thereof) is set by expectations of the future (expected discounted value of cash flows). The first one is a flow view, but the latter two are stock views (respectively quantity and quality of stock).

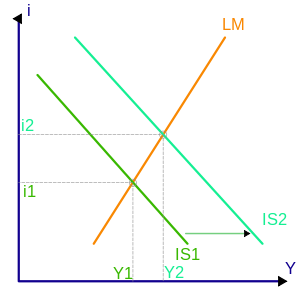

In order for each of these stock views to reconcile with the money view, they introduce models to determine how the quantity of money should react. In the economics view, the Investment Saving / Liquidity preference Money supply model (IS-LM) determines what happens to the interest rates over time (as shown in the left side graph), and in the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) the relationship between its risk averse and risk tolerant participants vice versa the market portfolio and the underlying asset pricing is what drives the quantity of money (as shown on the right side graph).

In order to match the finance view up to the money view, these principles are considered:

- Market liquidity (ability to buy/sell large quantities without affecting price) depends on a dealer system.

- Ability of dealers to supply depends on their proper capital and funding liquidity.

- The ultimate source of funding liquidity is the Central Bank.

Conclusion14th of December 2016 |

|

This course beautifully bridges the divide between Economics and Finance by clearly elaborating on the money view and the importance of market dealers. For me as an economics enthusiast without any formal training in the subject matter, it has come to form my fundamental understanding of money flows in macro-economics. The course is presented in a suitable fashion with lots of connections to events we have all lived through in recent years (housing bust of 2008, Euro Crisis…), making it all the more clear how the world (of banking) works.

| Review | Financial Sector |