Reimagining Management -

20th of May 2019 |

|

The goals of BPM have nonetheless stood solid ever since the discipline was introduced:

- to help organizations realize their strategic objectives and value propositions.

- to create, accumulate and deliver value to the customers through collaboration.

- to focus every part of the organization on this value delivery.

- to help managers manage their day-to-day operations as well as their focus on the future.

- to support all in the organization in their work activities.

|

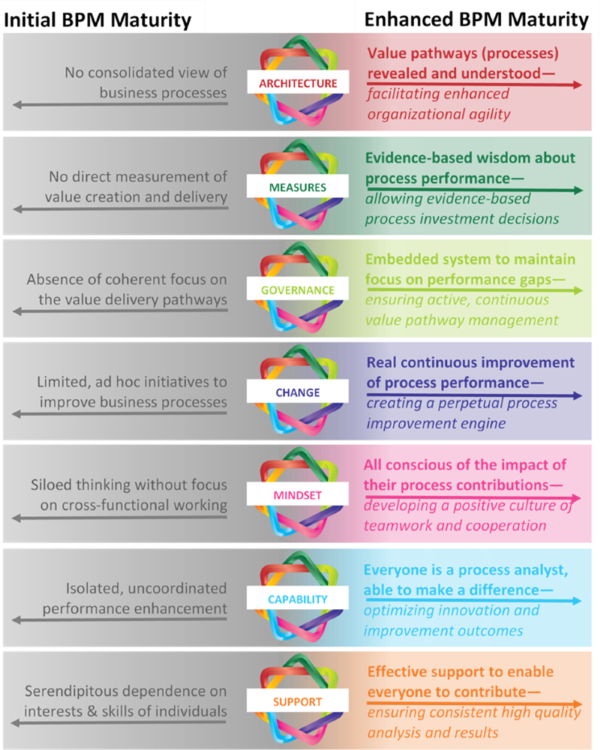

The book focuses on the 7Enablers of the BPM-framework (architecture, measurement, governance, change, mindset, capability, and support). The framework stresses the fact that each of these must be present and developed for BPM to resonate with the company culture and enable the creation of a widespread systemic approach to value delivery. These 7Enablers should be simultaneously cultivated, and for this endeavor the book suggests the use of the Tregear Circles, developed by the author for this very purpose. This is reflected in the structure of the book, with a chapter dedicated to each of the enablers, and a 9th and 10th chapter to culminate in the use of these Tregear Circles. Chapter 1 sets the stage for the rest of the book: What is the problem we try to solve? Organizations need to deal with major changes to both their operational and strategic reality. And both the complexity and frequency of these changes are ever-growing. Examples of these changes: radically increasing customer expectations, sector and business model disruptions, intensifying competition, … Since most traditional management is formed by the organization chart and their associated functional areas with the obvious resulting fragmentation, the majority of management effort is focused on individual areas, with collaboration across functional domains (and in some cases across companies) being treated as an afterthought. This needs to be addressed with clear links between strategy and operations in order to reach a full(er) potential of value creation. Both potential problems with and characteristics for proactively improving performance need to be on the radar of management. |

The primacy of the process in management is the fundamental concept for leveraging processes as enabler of change and agility when properly managed. Separate functional areas of an organization are unable to deliver value to customers outside said organization, so the strategic intent of the organization needs to carry over multiple of these functional areas. In essence, this is done by installing mechanisms for identifying, measuring/reimagining, managing and improving organizational performance instead of individual business unit performance. Combine with this the need to understand to difference between current processes and future ones in order to successfully establish transformation initiatives to increase performance and respond to changing markets.

The key parts to achieve proper value creation are as follows:

- Strategy: Organizations want to deliver value to their customers and stakeholders.

- Process: Organizations perform a series of coordinated activities across a number of organizational domains to achieve this value.

- Process Management: A coordinated view of the performance of all processes is needed in order to optimize these processes.

- Execution: Process Management focuses the organization on activities that create and deliver this value as described by the strategy.

Combining these elements, according to the author, the raison-d’être for BPM is that business processes in that they are the collections of cross-functional activities, are the only way to deliver value to external customers and other stakeholders. I reiterate that while I believe processes to be one of the better ways to achieve this, I cannot accept it is the only way.

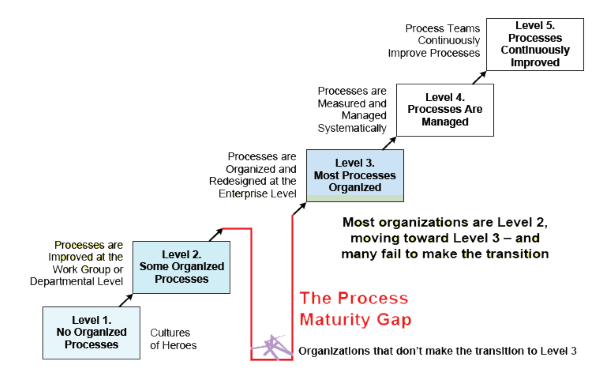

Next to managing business processes, the maturity of an organization in managing them can also be measured and improved. The maturity comes in five stages analogous to of SEI’s CMMI specification, which are the following:

- Non-Existent (Level 1): Little to no deliberate process management with no process documentation to speak of.

- Isolated (Level 2): Process management is increasing with process documentation and isolated cases of process improvement and performance management.

- Emergent (Level 3): Management has shifted to a process view with improvements happening cross-functional and organization-wide. Process architecture is used for decision making and a formal BPM group has been established.

- Consolidating (Level 4): The process approach results in significant performance improvements, and all key processes are being measured and have a process owner. Several improvement initiates are ongoing. The formal BPM group is actively training, modeling and coaching the organization.

- Ubiquitous (Level 5): Process Management is an intrinsic part of the culture and practice. A well-managed process architecture is constantly being used with performance of the processes being tracked and reported for maximum process change benefits.

Upgrading this maturity to a higher level is tightly linked to improving the 7 enablers. The diagram below shows us in rough guidelines what to each of these enablers can contribute on on every level of maturity. This is also elaborated in a blog post by the author.

It is paramount that all stakeholders realize that transforming a corporate culture into adopting process management does not happen overnight. It takes time. But on the other hand, the starting phase of this transformation does have a sense of urgency to demonstrate benefits before the initial hype dies down. The success of this type of transformation is directly proportional to the enthusiasm of the senior executives that are sustaining it. It is advisable to use the rules of threes when determining the timing for such an undertaking:

- Three weeks for initialization work.

- Three months to establish key structures and identify benefits.

- Three years to embed significant cultural change.

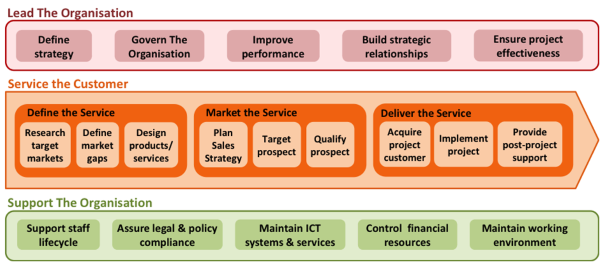

Chapter 2 addresses the first of the 7Enablers: Process Architecture. The architecture documents the organization’s processes and related resources in a hierarchical model to be used as a visualization, communication and management tool. Typically, processes are divided up into process categories such as the core processes in charge of value delivery (those with a direct connection to the customer), shared management processes used for high-level management decision-making and planning, and shared support processes that enable the other processes. An example diagram is shown below with the core processes in between the management processes on top and the support processes underneath.

When applying the logic of the primacy of the process that organizations can only generate value through cross-functional business processes, it stands to reason that strategy development, typically a top-down activity in contrast with BPM which is typically a bottom-up or middle-out activity, must also be executed via the processes of the organization. Developing a business strategy is generally about answering three questions as an organization: “Who are we?”, “Who are our customers and other stakeholders?”, and “What do we do for each other?”. More on strategic development can be read in my review of the “Balanced Scorecard”.

The process architecture allows for the focus of an organization to value delivery by visualizing the processes with their interdependencies and exposing the value pathways throughout the organization. It also allows a formalization of the deliverables for each of the processes. Once formalized, communication about the three questions can permeate the organization and its external partners and answers should consolidate in an information repository. Performance management is possible with the architecture by communicating process-performance information to all stakeholders, defining interfaces to external parties, prioritizing improvement activities, and coordinating with process project/portfolio management. As a byproduct, the organization gains an excellent tool to stress-test the reality of the organization’s vision, mission, and other strategy statements. To be able to leverage the capabilities granted by an elaborated process architecture, it should be communicated to all stakeholders, kept up-to-date and should be actively used, or it quickly loses its value.

It is important that strategic, tactical and operational decisions are based on these measurements. Otherwise proposed process improvement initiatives will not be taken seriously by those in charge. These measurements indicate the health of an organization, identify the concerns that come with this measured health, and show the progress of recovery from what ails processes inflicted with performance issues. Continuously gathering process measurements and reporting on these measurements gives management and the organization in general the benefits of making decisions with a factual foundation. Linking these measurements to the value processes deliver and to whom it delivers this value, a clear view can be established of which measurements are critical to our stakeholders, granting insight into customer-service levels and indicates which improvement priorities exist. Without measurement, process analysis and improvement efforts happen on gut feeling, and offer little benefit for the effort spent.

If need be, a drilldown into the functional measurements could give further insights about measures taken at the process level, but normally the process level measures should be sufficient if the process architecture and related measures are well defined. The author suggests utilizing the Leonardo ProMeasure methodology which he developed for this very purpose, which divides the task of finding valid process-performance measures into multiple phases, each with several steps. These phases are: “Select the process”, “Determine Stakeholders”, “Determine measurement themes/candidate measures”, “Verify validity of the measures”, and “Record the measures”.

There are any number of barriers and pitfalls that can hamper proper measures, of which the most detrimental would be to have a corporate culture aimed at using these measures to play a blame game. This will instill in people a desire to not measure accurately, but rather in their favor, and this sort of misinformation undermines the validity of the process improvement work. Other such barriers can be inappropriate measures, measures disconnected from value creation, lack of accountability for gathering these measures, lack of confidence in the gathered measures, … Each of these can be met with countermeasures to be specified in the improvement initiatives and should not be taken lightly. These countermeasures can become the pillars for the success of the entire BPM project.

The main goal of process improvement is to achieve the organizational goals. This requires a thorough understanding of cross-functional performance, and not just the performance of your processes and/or segments of the processes. This understanding can only come from continuous process improvement efforts which necessitates continuous assessment followed by the appropriate responses. The causal chain as stated here moves us along to chapter 4: Process Governance.

Process governance is a form of oversight needed to deliver on the core objective of improving cross-functional process performance. After measurement has been determined and numbers have been gathered, the organization has the basis for actively developing continually improving its value-producing processes. It is all about managing the business process management, with a focus on how to collectively and individually exercise control over processes in a cost-effective manner. To be able to do this in an effective fashion, the organization is going to need a systemic approach to make processes documented and well-understood. This in turn will result in more leads for optimization opportunities and a higher success rate in improving the selected processes. Process governance can be broken down into five streams, managing for the other enablers of BPM:

- Performance Management: formulate targets, design measurement methods, analyze and report results.

- Idea Management: Nurture discovery of innovative ideas, assess their impact and prioritize changes.

- Anomaly Management: Identify performance concerns, analyze causes, determine solutions.

- Improvement Management: Oversee process changes, review change initiatives.

- Model Management: Assure process-model quality, oversee modelling conventions compliance.

Process Governance is about reimagining and responding to process performance anomalies and innovation opportunities, and generally about keeping the process healthy. Good Process Governance forces an overlay of roles and accountabilities within an organization over the existing organization chart, complementing the traditional reporting, authority and delegating structures with cross-functional collaboration. The typical process governance framework will have three elements: process ownership, process authority (for example a process council) and process support (for example a BPM Office or Centre of Excellence).

Process owners can be assigned to any process in the designed architecture. Their task is however not to be responsible for the performance of the process, which is nigh impossible, as it spans multiple departments and business units. Their accountability does not lie with the performance of the process, but with the appropriate response to process-performance reports. As such, a process owner has no operational involvement in the day-to-day execution of his processes, but rather with a methodical follow-up and response to changes in performance and/or process performance requirements. The process owner needs to have a plan to tackle performance issues and have people tasked with performance interventions. More in detail, the duties of a process owner are the following:

- Assist with the formalization of the purpose and vision of a process, and how it relates to organizational strategy.

- Create an environment to make the process performant according to its targets.

- Set up a performance measurement with measures and measurement methods.

- Understand possible gaps with target performance and have grasp on possible improvements with their effect on this gap.

- Nurture process innovation.

- Management of risks to the process and its performance.

- Change Management of the process.

- Process performance reporting to the appropriate stakeholders.

- Promote BPM by exemplary management of processes.

- Appoint lower-level process owners if required.

- Increase process awareness in the organization.

The process council provides the whole-of-organization coordination and oversight to create and sustain an integrated approach to BPM. Typically, this council is formed by members of the C-level, senior managers, high-level process owners and the manager of the BPM office. These members are needed for buy-in, as the council deals with insuring that processes deliver on their benefits for executing organizational strategy. The council’s main focus is:

- Maintain linkages between process management/improvement and execution of strategy.

- Ensure action is taken on process performance anomalies and opportunities.

- Monitoring of improvement initiatives for realized benefits.

- Develop BPM approach policies and start initiatives for increasing BPM maturity.

- Resolution of possible high-level misalignments and conflicts between improvement initiatives.

Relating to the last point of the council’s focus: Process dissonance can occur between process improvement initiatives, so process change should be a collaborative effort in the form of a program. This collaborative effort is shaped by the level of authority given to the process owners. Here we have two models: First, the process owner is the formal design authority and no changes can be made to his processes without his explicit consent. The second model is the process owner being the voice of the process, defending his priorities and targets, but process changes are deciding in a committee of process owners. While both models have benefits and drawbacks, the second model is not always possible in all organizations.

Process Governance is one of the hardest enablers to enhance within an organization. Next to specific barriers that might exist in an organization, a common set of barriers to effective process governance can be listed: Struggle to get engagement, governance process can be too complicated, governance roles can be unclear, implementation failures occur with some frequency, and the aforementioned conflicts between individual process owners. These need to be tackled as soon as they pop up, and for the common ones maybe even preemptively.

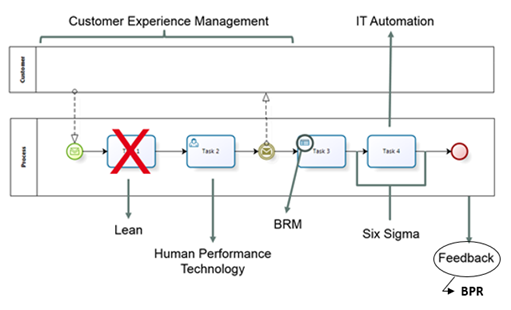

Where process governance is the follow-up of process performance, process change (chapter five) is continuously finding ways to remedy anomalies with performance and attempting to address the gap with the performance target through ad hoc as well as systemic changes. It acts on the problems that occur and capitalizes on opportunities. It is the heart of BPM. If you are not going to be continuously improve on processes, the overhead of BPM is just waste, and by its own principles should be eliminated. Several methodologies exist to determine which changes (6Sigma, BTrends’ Business Process Change…), and I have spoken about them at numerous occasions in other articles. As such, the author states that the process of process improvement should be the most efficient and effective process in the organization. A caveat in the book is that continuous improvement does not mean rapid improvement. While rapid changes can cause a significant improvement, it can on its own not be considered a systemic approach.

When formalizing gaps and seeking answers to it, the SWOT technique dealing with Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats is usually employed. Another way to handle these is the 4Dimensions model, which identifies these dimensions:

- Enhancement: changes the process in the way objects, assets and resources are used, or changes to customer involvement.

- Innovation: radically change the process (reimagining), questing and challenging all assumptions behind its design and operation. This distinguishes from Enhancement through the degree of change (incremental vs radical), and the source of the change (performance-driven vs idea-driven).

- Utilization: Examines people, data and systems involvement in the process to find more efficient ways.

- Derivation: Takes to heart the lessons learned of others through reference models, benchmarking, case studies and other published sources.

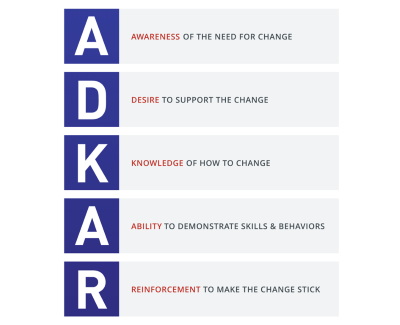

Managing change also has numerous methodologies associated with it, such as ADKAR from Prosci and the 8-Step Process from John Kotter. The author does a short explanation of their main principles, but I will leave it at the illustrations below that give a quick overview of these principles.

Process Mindset is enabler number 5 and chapter number 6. IT deals with corporate culture and making sure the organization promotes the concept that its people and their teams are conscious of the processes in which they participate. The likeliness of people participating in process-centric management is greatly increased if they know how this will impact them and their daily work, and how they are contributing to the goals of their organization. The return of such an awareness is process management excellence. The goal of increasing the process mindset is not to create process theory zealots, but rather enabling changes in the way people work: How it is designed, undertaken and managed.

The characteristics of a process-aware organization are measurement-friendly, community-focused, quality-motivated, change-welcoming, challenge-addicted, and action-oriented. In short, the process mindset allows for process improvement beyond ad hoc attempts, with sustained systemic approach to deliberately and continuously discover opportunities for improvement. Getting your organization as well as the people in it on board with all of these adjectives can be done using different techniques, such as for example process innovation jams or idea submission capabilities, but is never a one-off project. Continuous reinforcement of the mindset is needed to keep all on board with the idea that BPM is valuable with worthwhile benefits.

The key requirements for effective leadership in maturing process mindset are having a clear vision, honesty and openness about the consequences/implications of process changes, commitment to achieving the vision, and situational awareness about the daily operational dealings and being able to adapt plans as required to achieve effective change. Common barriers for this enabler are: Overemphasize the theory over the practice, inconsistent communication, ex cathedra explanations instead of selling the approach, information overload, lack of practical purpose, and focusing on modeling/artifacts instead of applying the improvement approaches.

Process Capability (and chapter 7) is all about increasing support to be able to do proper process management: investing in the proper tools and teaching the people the necessary skills to be able to identify, analyze, improve and manage the business processes (in other words: the process lifecycle) and to become a catalyst for change. This increase can be achieved through training and/or practice. Practice generates experience while training introduces new capabilities. The trainings can be either formal or more impromptu (such as inviting key note speakers, attending conferences, knowledge sharing between team members…)

There is an entire list of required capabilities that need to be understood by a large number of people to achieve a notable level collaboration on the business processes:

- The general principles of BPM

- Process improvement and management methodologies

- Project management for process projects

- Process change management

- Process Modeling and Analysis Conventions and Tools Use

- Ideation techniques

- Innovation Management

- Process Automation possibilities

- Performance measurement purpose and logistics

- Process governance arrangements

- Communication plans between collaborators

- Data analysis

- Conflict resolution

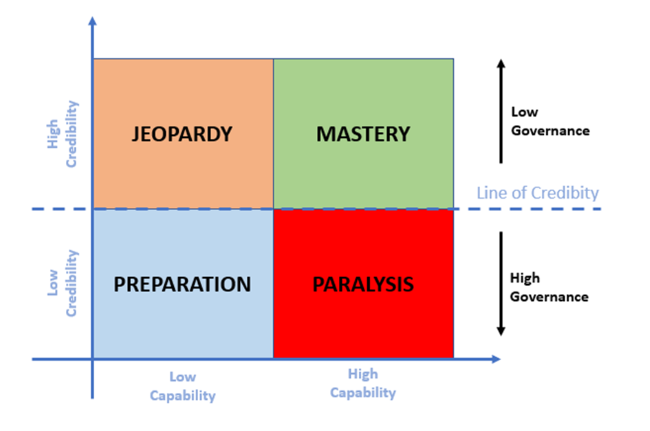

In order for capabilities to serve their purpose, they need to be accompanied by a degree of credibility. This credibility is established by both those people seeking to initiate process change, and those that will be affected by these changes. They have to have the confidence to submit key processes for review. If credibility in a certain group is low, this hampers further capability development.

The relationship between capability and credibility can be presented as a quadrant with 4 levels, that are split up by the “line of credibility” indicating the trust that is placed in the advocates of the process change by the various business managers. The levels are the following:

- Preparation: The common starting point for any BPM initiative: Both capability and credibility are at a low level.

- Mastery: The other extreme. Both high capability and credibility are high indicating the organization is capable of significant and sustainable process management change.

- Paralysis: The advocates for process change have the necessary skills and tools, but fail to convince widespread adoption, resulting in low credibility.

- Jeopardy: Low BPM capabilities (lacking skillsets and tools) are not recognized in the organization, but there is a widespread belief and credibility resulting in overly ambitious projects doomed to fail.

The path to Mastery, or the perfect state of the organization for process change, is about increasing credibility together with developing the necessary capabilities. This boils down to an internal marketing process, selling the process change to large audience. There is no better marketing strategy than to report on successes. Success breeds success, as the saying goes.

Getting an organization’s capabilities to the required levels is one thing. Providing process support for the development, sustaining and realizing the benefits of process-base management is what chapter 8 is about. This support should be centralized in an entity that doesn’t do process analysis itself, but rather makes sure that the capabilities are developed to facilitate this work. It should report to a senior executive (sponsor of the entity) with ready access to the CEO, or even the CEO him/herself. This entity has been called many things, but let’s stick to BPM Center of Excellence (CoE) for this review. The services provided by this CoE are:

- Supports all stakeholders in process management and improvement such as for example the process council in charge of governance and the process owners.

- Enabling the use of process improvement methodologies.

- Ensuring compliance with determined standards and testing the quality of the process modeling.

- Maintaining BPM artifacts such as the process architecture and modeling conventions.

- Coordinating BPM activities, measuring BPM maturity and evaluating process improvement realizations.

Since the CoE will always be a cost center, and more of an enabler to achieve benefits elsewhere, it should be made clear how to evaluate what the effects of a smooth-running CoE are. The benefits of setting up a CoE are the following:

- Streamlined business processes, which in turn increase operational effectiveness and efficiency

- In-house development of capabilities without reliance of external parties (for example through standardized training and knowledge sharing) and higher BPM maturity throughout the organization

- Consistent, repeatable and reliable approaches for process analysis and management, resulting in a greater success rate for process improvement initiatives

- Optimized innovation management

- Optimum utilization of resources which in turn reduce operational costs

- Improved reporting of process performance and better decision making based on these reports

- Better alignment of corporate strategy and processes to increase productivity and agility

- Improved ability to develop and carry out effective digital strategies and IT projects

There are different modes in which the Center of Excellence can operate. The directing mode sees a CoE with a lot of authority to intervene in business unit operations and enforce the compliance to BPM standards. The serving mode sees a CoE responsive to requirements and advises on outcomes and acceptance of BPM guidelines without enforcing them. The coaching mode is the middle ground between the first two modes where the CoE has limited powers of coercion, but recognizes that business units participate as volunteers in the BPM adventure rather than as conscripts, ensuring more buy-in.

Not establishing a CoE does come with several pitfalls for process-oriented organizations though. Here are of few of the problems such an organization might encounter:

- When there is no central entity coordinating the BPM activities, they are conducted isolated for each other, without simultaneous development of capabilities or even double work, leading to a diminished return on process investment and a harder adoption throughout the organization.

- The uniform reporting in order to collate evidence for whole-of-organization benefits also becomes more difficult.

- Without effective guidance, support and traction for new process initiatives becomes more difficult as sponsorship, resources and positive expectations are harder to come by.

- Consistency and sustainability of the processes becomes harder as none are concerned with optimizing the processes for process improvement.

With all seven enablers behind it, the ninth chapter focuses on the processes to get these capabilities to the level they need to be to make for a successful process-oriented organization. In other words, achieving cross-functional processes aimed at creating, accumulating and delivering value, and that are central to strategic, tactical and operational management. Just knowing the enablers doesn’t help you over the BPM Maturity Gap that Paul Harmon specified in his book “Business Process Change”.

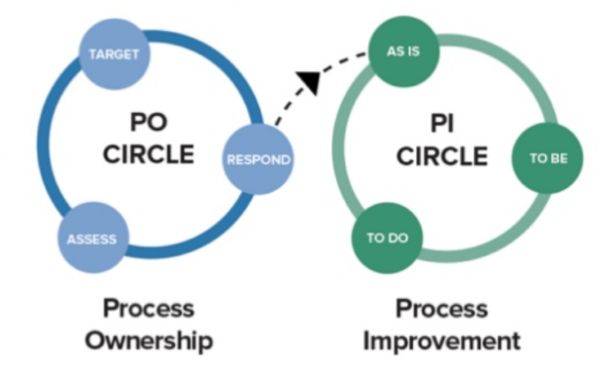

Roger Tregear offers a way to traverse this chasm using the Tregear Circles, a metamodel that can be pragmatically used to increase each of the enablers where needed. The first circle is the Process Ownership circle. This circle is about continuously testing performance of the processes to quickly spot emergent performance issues or innovation ideas. The circle consists of three key activities: Target – Assess- Respond. The second circle is the Process Improvement circle, with its own key activities: As Is, To Be, and To Do. As soon as an opportunity for improvement comes out of the first circle, its current state is assessed against what the target could or should be and appropriate action is taken, based on the evidence gathered. A successful application of these circles means the process owner will continually find opportunities for process improvement.

The tenth chapter is titled the “Big BPM Project”. This is a chapter on putting all knowledge accumulated in the previous chapters to use in an almost exercise-like way to roll out initiatives aimed at transforming an organization into a process-aware entity. To do this in a successful manner, six actions need to be taken:

- Focus on the 7 Enablers of BPM to shape pragmatic, integrated work packages into a coherent project.

- Set realistic expectations. BPM is an incremental discipline and shouldn’t be completed too quickly.

- Leverage interdependencies: Effective work on one enabler will positively influence work on other enablers.

- Get the Treager circles turning: Ensure stability through the momentum of improving the enablers into a self-supporting infrastructure.

- Make it real: Start off immediately with real processes with their current issues and opportunities.

- See the benefits: From the very beginning of this project, benefits should be made visible.

The project team for this endeavor have two groups: The development team that is tasked with the main work of the project and a reference team, comprised of senior managers and executives that act as an advisor to the development team. However, these teams aren’t the only stakeholders. A thorough stakeholder analysis should be done to determine all involved and how they rank on influence and authority compared to their practical involvement, giving us the following classifications:

- Principals: High levels of involvement and significant influence. These people are the key players in all project decisions.

- Bystanders: Low engagement, but significant influence. Although not involved now, they might become future principals and as such should be kept informed and satisfied.

- Followers: Low engagement and influence. Keeping these in the loop is of lower priority but should be monitored in case their classification changes.

- Connectors: Very engaged in the practical process executions but have little influence. They are a valuable source of information and a useful connection point to the rest of the organization.

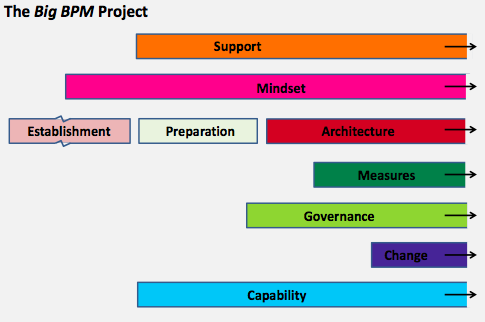

The Big BPM Project consists of many phases as shown in the diagram below. The first of these phases is the Establishment Phase where a clear and shared understanding of the reasons (linked to the corporate strategy) for this project throughout the stakeholder ecosystem. This understanding comes from compelling reasons reflecting the realities of the organization: its current BPM maturity, pain points and opportunities. Ideally, these compelling reasons are discovered, discussed, agreed upon, and formally documented. The decision-making process throughout this project will also need a pertinent structure. This is achieved by keeping the requirements up to date along the way, always documenting the why, who, when, how, what and where. resulting in an overall plan and intent. These deliverables will become the foundation for the remainder of the project and a basis for communicating with the stakeholders in the form of a communications plan or strategy. This marks the end of a successful establishment phase.

Once the Establishment Phase has completed, work in the Preparation Phase can start. This is a phase of about 2 weeks to arrange and confirm the logistics of the project and kicking it off. These are the nitty-gritty actions needed to get started: arranging interviews, booking office spaces, setting up a documentation infrastructure… During this time there are three other activities that can be executed:

- Individual information sessions for key stakeholders.

- Project discovery workshops involving the development team, reference team and others if appropriate.

- Project kick-off meeting involving all stakeholders.

The phases are then divided into a number of work packages for each of the enablers to be improved. These packages can be found as well on the author’s blog, and I might even make the effort to do this exercise at another time. The result of this project should have all enablers matured enough to support an organization to have successful ongoing process-based management.

The epilogue chapter of the book focuses on why organizations might opt not to pursue process management. The foremost reason being the blind sport reasoning: the absence of a systemic approach to BPM is and invisible management lack that isn’t seen unless you know what it is. This invisibility might be caused by any number of factors: lack of knowledge, lack of compelling reasons, lack of urgency, lack of insight… Another impediment in the form of change reluctance can also play a roll, such as for example fear of job loss or other disruptions.

As for my epilogue to this review, I am nothing but positive. This book is jam-packed with useful information and hands you a way of working to implement or transform a process-aware organization with clear tasks and objectives that give any who are in this field a roadmap on how to get the ball rolling.

| Review | BPM | Business Architecture |